On March 20, 2025, in an article in The Atlantic entitled “The Unbelievable Scale of AI’s Pirated-Books Problem”, Alex Reisner disclosed how META pirated millions of books and research papers to train their flagship AI model Llama 3 to be competitive with products like ChatGPT. Reasons for this illegal action is simply time; asking permission and licensing takes too much time and is too expensive.

On the same day, The Atlantic provided a link to LibGen (the pirated-books database that Meta used to train its AI) so authors could search its collection of millions of illegally captured books and scientific papers. I went there and searched my name for my novels, non-fiction books and scientific papers and discovered several of my works in their AI training collection.

Two of my many scientific papers appeared in LibGen under my scientific author name Norina Munteanu. The first scholarly article came from my post grad work at the University of Victoria on the effects of mine tailing effluent on an oligotrophic lake, published in 1984 in Environmental Pollution Series A, Ecological and Biological Volume 33, Issue 1. The second article on the effect of current on settling periphyton came from my M.Sc. ecology research published in 1981 in Hydrobiologia, Volume #78.

.

.

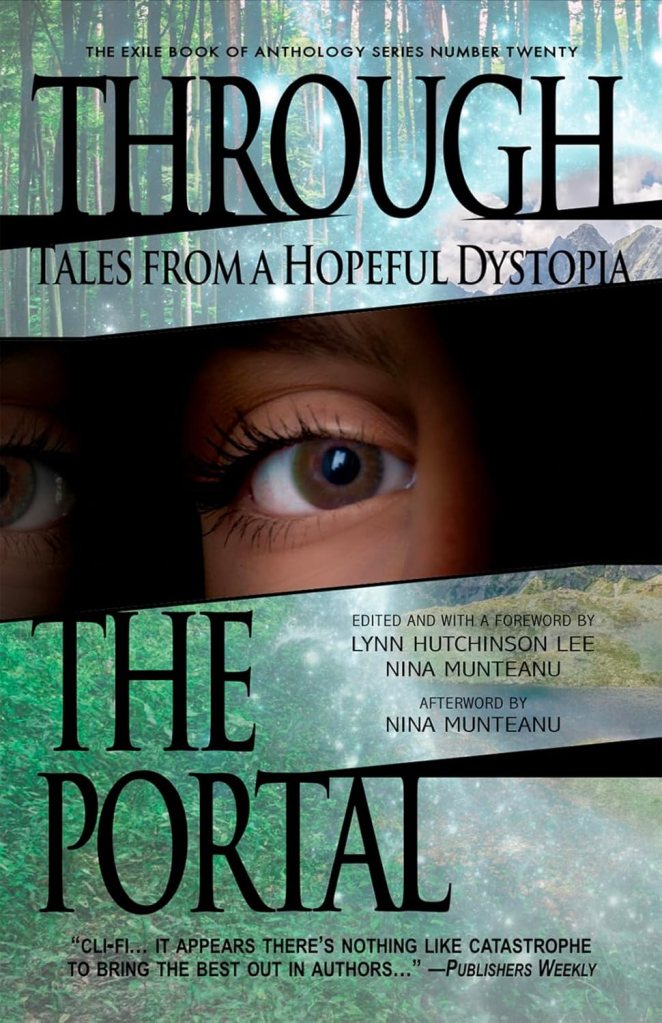

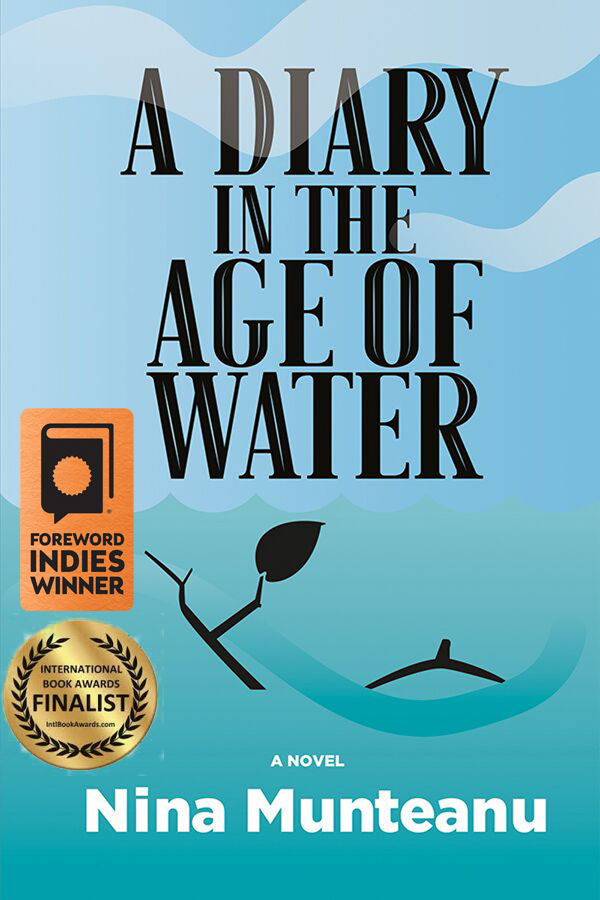

Three of my thirteen novels appeared in LibGen under my fiction author name Nina Munteanu. I found it interesting how their bots captured a good range of my works. These included two of my earliest works. Collision with Paradise (2005) is an ecological science fiction adventure and work of erotica; Darwin’s Paradox (2007) is a science fiction medical-eco thriller that features the domination of society by an intelligent AI community. The bots also found my latest novel, A Diary in the Age of Water (2020), a climate thriller and work of eco-fiction that follows four generations of women and their relationship to water.

.

.

.

Each of these works has been highly successful in sales and has received a fair bit of attention and recognition.

When Genevieve Dubois, Zeta Corp’s hot shot starship pilot, accepts a research mission aboard AI ship ZAC to the mysterious planet Eos, she not only collides with her guilty past but with her own ultimate fantasy. On a yearning quest for paradise, Genevieve thinks she’s found it in Eos and its people; only to discover that she has brought the seed of destruction that will destroy this verdant planet.

Recognition: Gaylactic Spectrum Award (nominee)

“Collision with Paradise is ideal for readers who enjoy dark, introspective science fiction that explores complex moral dilemmas and psychological depth within a lush mythologically-rich setting.”—The Storygraph

.

A devastating disease. A world on the brink of violent change. And one woman who can save it or destroy it all. Julie Crane must confront the will of the ambitious virus lurking inside her to fulfill her final destiny as Darwin’s Paradox, the key to the evolution of an entire civilization. Darwin’s Paradox is a novel about a woman s fierce love and her courageous journey toward forgiveness, trust, and letting go to the tide of her heart.

Recognition: Readers Choice Award (Midwest Book Review); Readers Choice (Delta Optimist); Aurora Award (nominee)

“Darwin’s Paradox is a thrill ride that makes you think and tugs the heart.”—Robert J. Sawyer, Hugo and Nebula Award winning author of Rollback

.

This gritty memoir describes a near-future Toronto in the grips of severe water scarcity during a time when China owns the USA and the USA owns Canada. A Diary in the Age of Water follows the climate-induced journey of Earth and humanity through four generations of women, each with a unique relationship to water. The diary spans a twenty-year period in the mid-twenty-first century of 33-year-old Lynna, a single mother and limnologist of international water utility CanadaCorp, and who witnesses disturbing events that she doesn’t realize will soon lead to humanity’s demise.

Recognition: 2020 Foreword Indies Book of the Year Award (Bronze); 2020 Titan Literary Book Award (Silver); 2021 International Book Award (Finalist).

“If you believe Canada’s water will remain free forever (or that it’s truly free now) Munteanu asks you to think again. Readers have called ‘A Diary in the Age of Water’ “terrifying,” “engrossing,” and “literary.” We call it wisdom.”—LIISBETH

.

The April 3, 2025 article by Ella Creamer of The Guardian noted that a US court filing alleged that Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg approved the company’s use of the notorious “shadow library”, LibGen, which contains more than 7.5 million books and 81 million research papers. According to Toby Walsh, leading AI researcher at the University of New South Wales: “As far as we know, there was an explicit instruction from Mark Zuckerberg to ignore copyright.”

This begs the question of the role and power of copyright law.

“Copyright law is not complicated at all,” said Richard Osman, author of The Thursday Murder Club series. “If you want to use an author’s work you need to ask for permission. If you use it without permission you’re breaking the law. It’s so simple.”

If it’s so simple then why is Meta and others getting away with it? For its defence, the tech giant is claiming “fair use”, relying on this term permitting the limited use of copyrighted material without the owner’s permission (my italics).

It would seem that just as Trump trumped the presidency, Zuckerberg and his AI minion bots have trumped the copyright law—by flagrantly violating it and getting away with it—so far (on both counts).

The actions of Meta were characterized by Society of Authors chair Vanessa Fox O’Louglin as “illegal, shocking, and utterly devastating for writers.” O’Louglin added that “a book can take a year or longer to write. Meta has stolen books so that their AI can reproduce creative content, potentially putting these same authors out of business.”

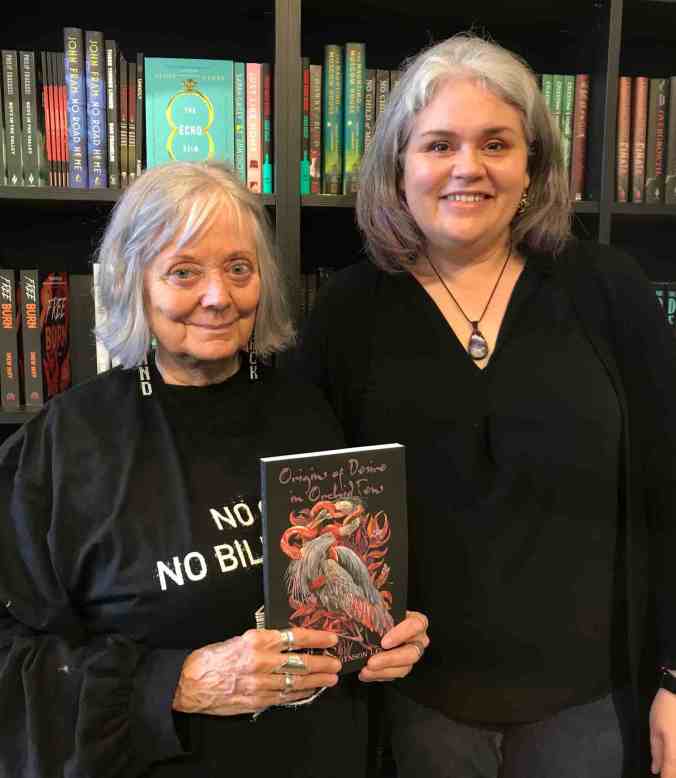

.

.

Reflecting many authors’ outrage throughout the world, Novelist AJ West remarked, “To have my beautiful books ripped off like this without my permission and without a penny of compensation then fed to the AI monster feels like I’ve been mugged.” Australian Author Sophie Cunningham said, “The average writer earns about $18,000 a year on their writing. It’s one thing to be underpaid. It’s another thing to find that [their] work is being used by a company that you don’t trust.” Bestselling author Hannah Kent said, “If feels a little like my body of work has been plundered.” She adds that this, “opens the door to others also feeling like this is an acceptable way to treat intellectual copyright and creatives who already…are expected to [contribute] so much for free or without due recompense.” Both Kent and Cunningham exhort governments to weigh in with more powerful regulation. And this is precisely what may occur. Nicola Heath of ABC.net.au writes, “the outcomes of the various AI copyright infringement cases currently underway in the US will shape how AI is trained in the future.”

According to The March 20, 2025 Authors Guild article “Meta’s Massive AI Training Book Heist: What Authors Need to Know,” legal action is underway against Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft, Anthopic, and other AI companies for using pirated books. The Authors Guild is a plaintiff in the class action lawsuit against OpenAI, along with John Grisham, Jodi Picoult, David Baldacci, George R.R. Martin, and 13 other authors, but the claims are made on behalf of all US authors whose works have been ingested into GPT.

The Authors Guild suggests five things authors can do to defend their rights:

- Send a formal notice: If your books are in the LibGen dataset, send a letter to Meta and other AI companies stating they do not have the right to use your books.

- Join the Authors Guild: You should join the Guild and support our joint advocacy to ensure that the writing profession remains alive and vibrant in the age of AI. We give authors a voice, and there is power in numbers. We can also help you ensure that your contracts protect you against unwanted AI use of your work.

- Protect your works: Add a “NO AI TRAINING” notice on the copyright page of your works. For online work, you can update your website’s robots.txt file to block AI bots.

- Get Human Authored certification: Distinguish your work in an increasingly AI-saturated market with the Authors Guild’s certification program. This visible mark verifies your book was created by a human, not generated by AI.

- Stay informed. The Authors Guild suggest signing up for the free Guild biweekly newsletter to keep updated on lawsuits and legislation that could impact you and your rights. The legal landscape is changing rapidly, and they are keeping close watch.

.

How do I feel about all this? As a female Canadian author of climate fiction? As a thinking, feeling human being living in The Age of Water? Well, to tell the truth, it kinda makes me want a donut*…

*as delivered by James Holden in Season 3, Episode 7 of “The Expanse”

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.